Down and out in Rome

“I’m destitute! Again!” I slacked Josh “Daddy” Quittner, the CEO of Decrypt, my one-time employer and personal editor. I was having one of those recurring moments of crippling financial panic.

This was around three months ago, and Daddy responded in his typical, good-natured way telling me that he didn’t care, that I was a lazy loser, a vile ginger and that I owed him money. Oh, we had a good old laugh about that one! But he was kidding, he later said, telling me that there might indeed be one decent idea squelching around in his fat head.

NFTs.

No, no—don’t groan. As I said, this was well before today’s current NFT mania, when even flatulence is being registered to the blockchain and sold as one of a kind.

When we first chatted at the beginning of the year, the speculative art craze was just starting to take root in the crypto world. Quittner pointed out that lots of semi-talented opportunists like myself were pulling in thousands (though not yet tens of millions) in cryptocurrency for “non-fungible tokens.”

These NFTs, he explained, were typically one of a kind digital representations cryptographically registered to the blockchain, that could be purchased from various online marketplaces in exchange for cryptocurrency, generally ether. NFTs were like cryptographic signatures that referenced a digital artwork, could not be duplicated and supposedly conferred ownership of the artwork onto the buyer.

It sounded utterly idiotic.

Previously, I had produced some obscene illustrations for a short entertainment called “A Crypto Carol.” Quittner observed that I was a “weirdly accomplished artist.” So he thought that perhaps Decrypt could offset the burden of paying me as a freelancer if I just sold a new artwork for thousands—and then wrote about it for him for the usual penny a word.

“I’ll pay you handsomely for ‘How To Make Your Own NFT and Get Crazy Rich,’ wherein you first-person the process and explain it so even I understand it,” he said. “Then you sell one. You’ll obviously make a fortune.”

A stirring idea—especially for a young man on the brink of mild ruin. I nodded grimly at the large, framed oil painting of Daddy that I keep on my wall. And thus began my deleterious voyage into the disturbing and venal world of NFTs.

The artist begins

How to make one, though?

“Ask that buzzkill Rob,” Quittner slacked gruffly, referring to Rob Stevens, the hunchback at the bellchamber of Decrypt’s editorial citadel, scarcely appreciated and broadly despised—though recognized for the cheerless discipline of his work ethic.

Begrudgingly, Stevens put me in touch with several artists, among them “Giant Swan,” a genial Australian who makes virtual reality art. Before I got too deep into this, I wanted to hear about whether one could indeed make any money in this racket.

Swan told me he had made a killing on the Origins Collection he had done in collaboration with the record label Monstercat. “I was thinking, if I get $10,000 out of this, I’ll be happy,”he said. I snickered at that ludicrous sum.

“But it turned over $190,000” he said.

Emphasis added. He didn’t really say it in that italicized, bold-faced way, but that is how I heard it.

“When you decide to go full time being an artist, you don’t expect to be turning over sums like that,” he said, as if to clarify things.

A mere ten percent in royalties went to the platform involved, which is now a sort of unspoken standard. By comparison, a traditional art gallery can take as much as 70 percent.

“One of the cool things about NFTs,” Swan explained, “is as artists we banded together and said we need to standardize [these royalties] now—before we get bigger.”

The number “190,000” reverberated in my head. It caused my eyes to water, my pulse to quicken, and my legs to twitch in wild, jolting spasms. I even may have moaned a bit. Think of all the bus tickets I could afford with a sum like that, I thought.

“You probably missed the boat on the dumb cash.”

“That would probably be enough to get me out of my debt hole,” I mumbled to Swan, explaining that I might be looking to sell something myself. I mentioned my huge, international Twitter following. “Can I rely on my star power to make a big sale, instead of, say, my ‘talent?’” I asked. “I can still muster tens of tweets on a post, but I worry that might not be enough…”

“You’ve probably missed the boat on the dumb cash,” Swan admitted, not unkindly. “The joke’s gone. I’m not sure how much ‘trash art’ moves now. There was, briefly, a counterculture where people were making the worst art”—here he gave one example, which is still a masterwork by my dismal standards—”just to see if they could move it. They were making money on volume rather than making any big sales. But we have people with big marketing campaigns behind them now.”

He paused and I could sense him reconsidering. “With a low Twitter following you’re kinda screwed,” he said. “I would make moves to integrate in that community as much as you can. Art that does well on social media does well. The whole scene lives on Twitter.”

“Perhaps I should focus on one insane collector with terrible taste,” I mused.

“If you find a whole supply of them, let me know.”

Which gave me an idea.

The making of a mark

My revelation was that it wouldn’t be enough to produce something merely good. Really, I realized that to find that lucrative “collector with terrible taste” I would need to get some sort of dull-witted influencer behind me.

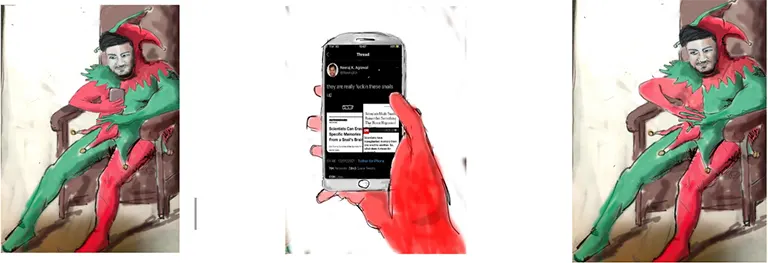

Luckily, Neeraj K. Agrawal was eager. A popular cryptocurrency “commentator” who apparently has some sort of communications role at the digital assets lobby group Coin Center but in reality doesn’t seem to do much other than tweet, Agrawal has always been a fascinating character to me: a manic tweeter whose oeuvre frequently betrays more than a hint of overwhelmingly desperate, unbearable sadness.

“Would you be down for a portrait?” I DM’d him, explaining my predicament. “Lol.”

“Lol,” Agrawal responded. “Sure fuck it. If this proves lucrative I’m open to posing nude.”

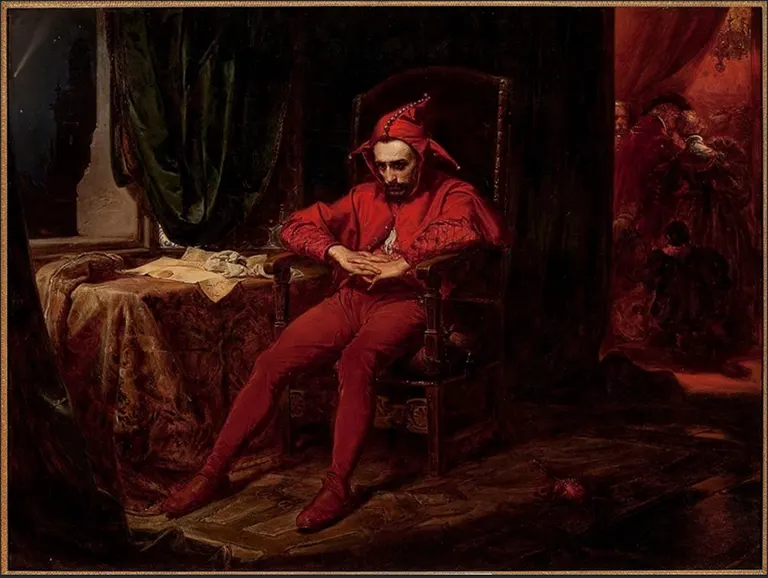

Mercifully that wasn’t necessary, and we eventually determined that the image I would create—which Agrawal, God willing, would tweet to his many followers—would be a rendering of him as a sad clown, clad in jester garb, hands folded, eyes cast emptily downward. Initially I had hoped to capture him like this, but he said his body “doesn’t move like that.” So instead we chose this classic, the idea being that I would sub in the clown’s face for Agrawal’s own clown face.

The photos he returned to me were quite something, and part of me wondered whether they wouldn’t have sold best on their own. (“I don’t need that out there,” explained Agrawal when I asked if we could include the photos in this article. “I can’t give these animals anything more to work with.”) But then how could I claim all the credit—and, indeed, all the winnings? I made a mental note to turn these photos in NFTs later, if the experiment worked.

“I’m thinking whether it’s better to photoshop your face or try and paint it,” I said.

Said Agrawal: “Let the muse work through your hands.”

So, using a white pad, a pencil and a black ink pen, I produced a quick portrait. Then I colored it using Photoshop, painting and repainting over all the mistakes I’d made on paper until it was acceptable by my low standards, adding in also the jester’s garb, which Agrawal hadn’t worn in the original pic.

Agrawal loved it.

Quittner wanted me to animate it. “It’s kind of boring,” the old pinchpenny wheezed. “Can you make him stand up and dance?”

Finding a platform

It was a relief to find out that the way to turn one’s artwork into an NFT was to decide on a platform that would host and sell the wretched thing. They would do the technical work, effectively registering the JPEG on the blockchain and handling the smart contracts involved in selling it. Most were set up in a sort of auction format, where the artist could offer the piece at a floor price and welcome bids for a set amount of time. Others, such as Foundation, offer royalties every time the piece sells in the future. The blockchain, as its sickening adherents love to say, is immutable!

These platforms, which are basically glorified hosting services, serve as both gatekeepers of and auctioneers to the NFT markets. While there have been a slew of scams and imitations, the best known among the marketplaces are Nifty Gateway, Rarible, SuperRare, and OpenSea. I thought I could persuade them to, you know, pull some strings and give me a platform, but none but Rarible, one of the less discriminating marketplaces, even bothered responding to my pleas for comment. (And I couldn’t be arsed to figure out how to work with a platform so that I could get an ongoing royalty every time my masterpiece changed hands in the future).

Promptly I found myself booking an hour-long conference call with Alex Salkinov, Rarible’s Moscow-born co-founder.

Salkin, who had clearly done well off the NFT mania and seemed to have rebranded himself as a sort of techno-philosopher (he kept turning the conversation to his notions around the “attention economy,”) told me that if I hoped to stand a chance on the NFT market I should host my work on his site, which would host virtually anything.

But he made it clear that I would have to play for real money here, that I couldn’t experiment and put the work up for, like, five dollars, since hosting fees alone would cost up to $100 worth of ETH. (“I’m not reimbursing you,” Quittner cautioned.)

Salkinov also made it clear that it wasn’t really worth animating the piece, or doing anything even particularly blockchain-y with it.

Some artists, for instance, embed functions into their NFTs that are extraneous to the work itself. For instance, a piece by the artist Mike Winkelmann, known better now as “Beeple,” changed depending on the outcome of the 2020 US presidential election. (It ultimately sold for $6.6 million.)

But doing that, Salkinov said, would require a dedicated platform and a grasp of complex tools, whereas Rarible was pretty much just a host for JPEGs and flash files. Although he allowed that the hosting software was complex enough for me to do something basic with it—for instance, embed instructions for a buyer to send me a message on Telegram and enjoy edit-privileges to the article you’re reading—I figured that would just open up a whole can of worms editorially. Quittner gets mad enough when people try to change his edits.

The prospect of essentially admitting my work was bad and just dumping it on Rarible was beginning to depress me, though, so I sought out Eleneora Brizi, an actual artist who had worked with the Chinese dissident Ai Wei Wi and has since turned to NFTs. More recently, Brizi organized an NFT exhibition in Rome which featured work by Giant Swan and the artist-duo Hackatao, in a thickly columned 16th-century church called San Salvatore in Lauro, just by the Tiber. The exhibition had ended in October. Veteran newspaperman that I am, though, I visited on my bike to verify that the place was real.

“What I like to do is sort of trick people,” said the affable and enthusiastic Brizim, referring to the October exhibition. “When I thought about Italian people I thought, ‘Where is a space where we feel comfortable and we know the aesthetic, the backgrounds, where we don’t have to think about it? And I thought, somewhere sacred. So I chose a church, knowing that people would come here, immersed in a kind of beauty that they know.”

I told Brizi about my own plans to make an NFT, telling her I’d spoken to Alex and Rarible, and she demurred. “There is a reason why Rarible spoke with you,” she said darkly. “Pretty much everybody gets their art on there, there’s not much curation.”

She told me to check out OpenSea, where an artist can build a genuine profile and following.

I mentioned my utter lack of talent and told her about my brilliant Agrawal marketing gambit. “He has 100,000 followers on Twitter,” I said. “If he tweets my work, surely some idiot will want to buy this thing…”

“You want to trick someone?” Brizi said, unimpressed. “It sounds a bit speculative.”

“Does that disgust you?” I asked.

“Noooooo,” she said. “I’m just not interested.”

Wanting to recoup some of my dignity, I looked into OpenSea as she suggested. The site is open to everyone but tends to favor artists who want to endure and build a following, rather than become lousy, one-hit wonders. Taking her advice I decided to set up an account and arrange four pieces in a beautiful collection titled, “Neeraj the Entertainer.”

Minting an NFT

I was worried that this part, actually turning a thing into an NFT, would be tricky. First I would have to set up an OpenSea account … then a wallet to handle the assorted set up and gas fees … then I’d have to load the wallet with funds…

But I realized that all this was sadly necessary if I were to receive my due. Some day soon, that wallet would be the repository of an astronomical fee from a discerning, deep-pocketed buyer. And my career as an NFTer would be launched.

For some reason, the flagship Ethereum wallet MetaMask wasn’t working for me. I tried another, Bitski, a wallet specifically designed for NFTs. But, Bitski wanted me to top it up using an external payment processor called Wyre. I needed at least $150 in my wallet to pay for hosting, but the damnable Wyre decided not to work across any of my debit cards!

Stressed beyond belief, I contacted an Italian NFT friend, Mattia Cuttini (his real name.) Cuttini had wild feelings of guilt after cancelling a trip I’d planned to Udine, his hometown, in which I’d planned to write some pretentious twaddle “juxtaposing” the region’s Renaissance history with its present role as a sort of Italian NFT hub. The ordeal had cost me €70 in non-refundable train tickets.

Preying on his conscience, I asked him to send some of his own ETH directly into my wallet, and he obliged. I paid him back via PayPal.

Sufficiently funded to stake my art, I mulled over whether to upload the series as a “bundle” or individually.

Individually would allow for a real bidding process whereas the “bundle” came at a fixed price. No idea why bundles couldn’t be set for auction bids, but it wasn’t an option. Since publishing my works singly would require four individual hosting payments, coming to at least $400 it seemed like a massive risk—especially given Daddy’s tight fists!

I opted for the bundle, setting the price at $4,000, which to me seemed to project the confidence necessary to convince potential collectors that it was a good, re-sellable investment, while also being sufficiently low to suggest some degree of humility and ineptitude.

So after dealing with the knotty pricing question, I got everything ready to go, pushed “sell” and clicked a button that “authenticated” my digital signature. And just like that, the bundle known as Neeraj the Entertainer was for sale.

“Eureka!” I shrieked. My bundle was now an NFT duly logged onto the Ethereum blockchain. The image, of course, is still available for all to see/screenshot, and the purchaser doesn’t actually have any greater claim to it than anyone else.

The gavel falls!

I gave Agrawal a heads-up. Then I tweeted the link to my Followers, every one of whom I imagined receiving the news with a kind of feral excitement: “Delving into the world of NFTs for a longform piece,” I wrote. “Have an exclusive collection of real-life portraits of @NeerajKA on sale as part of that effort—resulting article will describe the events leading up to whatever the hell this thing is.”

Agrawal tweeted his support, writing, “my pal @Ben_Munster is writing about NFTs. Being the artisan that he is, he fully dove into the story by drawing original artwork depicting my life. Now he’s selling it.”

“Likes” flooded in thick and fast—I garnered almost 10 Followers in the space of an hour, and at least one person commented. The thing was going viral.

I started thinking of the bus tickets I could buy. Why, with the money I was sure to make, I could hitch a ride to the supermarket if I wanted!

Yet, something was clearly awry. Despite Agrawal 100,000 followers and my own few hundred…there were no buyers!

Not so much as an email sniff over the transom came in. It was perplexing. I returned day after day to stare hatefully at the NFT. I mean, it wasn’t the Mona Lisa, I’ll grant you that. But it had its charm. Perhaps I should have made that useless Agrawal dance…

A fool and his money

And then on perhaps my 30th visit, I realized my error. I’d set the minimum price not at $4,000—but 4,000 ETH. That was $6 million at the time.

Whether that was over or perhaps underpriced I would never learn: Quittner ordered me to lower the price to something more reasonable, so I went for 0.28 ETH ($500) and put it back on the market, getting Agrawal to retweet it again.

“Actually you would have to pay me to take this NFT,” someone wrote in the comments.

“How much?” I asked.

Yet, things went far better this time. Within minutes, I found a buyer. Well, “found” is not quite right. Without any prior communication whatsoever my artwork changed in status from “on sale” to “no longer available.”

I put out a call, via Agrawal, for the buyer to get in contact with me, to no avail. Was it a crypto whale? A Romanian art dealer? An Agrawal Supersimp? My old patron, Joseph Lubin, the ConsenSys chief executive, perhaps? My mother? Mike Dudas?

That whole aspect of the sale, in a way, was as mysterious as it was heartbreaking.

While I could still look at my artwork on OpenSea and indeed on Photoshop, I felt a genuine sense of loss knowing some anon had purchased this vague form of ownership over it, even if it was only represented by a cryptographic hash on a certificate.

I hadn’t even bothered to animate my “painting,” and there was absolutely nothing distinct whatsoever about “owning” it via the blockchain rather than looking at it, but still. Looking at the collection now feels somehow different, alienating. I know that I could never bring myself to put it on sale again, as there is a genuine sense of it having been one of a kind, total shite though it may have been. (Ed.: Oh, it was.)

Former philosophy undergrad that I am, I began to theorize that this is precisely the reason wealthy people like to splash their money around public spaces. Being able to attach one’s name to something in the public domain—a bench, or a plaque or whatever—feeds the bourgeois ego.

“Damn this capitalism!” I yelled at Daddy’s portrait. “Reifying our very reality and turning public goods into mere commodities! Scrawling its grim signature on the very air we breathe! And now it seeks to gentrify our final refuge—our memes!”

Then I looked at my Bitski wallet: .28 shiny Eth winked lasciviously at me.

I had, at least, made enough money to pay almost a month’s rent. That’s $350, minus hosting and Photoshop subscription fees. Yay!

“Cheers, lad!” said Quittner brightly, who, when making money often talks to me in a style of English he learned from watching Basil Rathbone-Sherlock Holmes movies as a child. “Well done, on the sale, I say!”

“Ugh,” I whinnied. “I feel dirty, soiled. Truthfully, my ‘artwork’ was not very good at all, and shouldn’t have commanded $0, let alone $500. Just like that toss which sold at the Christie’s auction house the other week wasn’t worth $69 million. I feel like a scammer by association!”

“Don’t be an imbecile, my good man!” comforted Quittner. “You’re a paid professional whose work has been widely received in the marketplace.”

“What?”

“Besides, you owe me $100—”

“—?”

“I said I’d pay you $400 for the piece,” Quittner hastily explained, “but you’ve already made $500. And, like you said, that was wildly inflated. And because I take full credit for setting you up with this, that means you owe me the excess! So we’ll split the profit— send the $100 via PayPal, eh, wot, my good chap?”

That dirty dog! But, of course, Daddy was right. In the long run, I imagined, that’s how this whole thing will probably pan out. The market will die down and artists will stop making obscene amounts of money, and they’ll be left with nothing but exorbitant gas fees and hefty invoices from unscrupulous, opioid-addled, sexual degenerate editors.

Just as I was mulling this Quittner himself sent me another urgent Slack. “Got another idea for you old boy!” he said. “Remember those illustrations you did for ‘A Crypto Carol,’ eh, lad? I bet they’ll fetch a rude price on OpenSea. I’ll split the profits with you, of course—70/30.”

I considered it. Those illos were just moldering, mostly unseen, on my Substack. And I could use the money.